Dramamine

"Generic dramamine 50 mg online, medicine 8 capital rocka."

By: William A. Weiss, MD, PhD

- Professor, Neurology UCSF Weill Institute for Neurosciences, University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, CA

https://profiles.ucsf.edu/william.weiss

The internal trigger? hypothesis is contrasted with the social zeitgeber theory 50 mg dramamine with mastercard medicine for diarrhea, an external trigger? hypothesis (see Fig generic dramamine 50mg on line treatment yeast uti. In this review purchase 50 mg dramamine overnight delivery treatment zoster, we use the social zeitgeber theory interchangeably with the external trigger hypothesis order dramamine 50mg on-line treatment 8th february. Evidence for each proposed causal link of the social zeitgeber theory, or the five associations numbered in Fig. First, we review the association of life events, social zeitgebers and rhythms, and mood (see Fig. Next, we discuss the association of social and biological rhythm disruptions (pathway 3 in Fig. In each section, we specifically discuss how the findings pertain to the internal or external trigger hypotheses, or both. We begin by providing necessary background on the definition and assessment of mood disorders, life events, social zeitgebers, social rhythms, and biological rhythms in this literature. It is also possible that individuals may experience less severe episodes, or minor depressive episodes, which require fewer symptoms as well as a shorter duration and less persistence of these symptoms (see Research Diagnostic Criteria; Spitzer, Endicott, & Robins, 1978). The majority of the studies reviewed only included individuals who had experienced major depressive episodes in their study groups; however, some studies did not make a distinction between participants who experienced minor or major depression. We will make this distinction whenever possible in reviewing the studies, as some studies did find differences between these subtypes. In short, we categorize individuals who have experienced a major or minor depressive episode (but not a manic or hypomanic episode) as unipolar depressed. Individuals with bipolar disorder experience hypomanic or manic episodes as well as depressive episodes (although a depressive episode is not necessary for a bipolar diagnosis). Individuals diagnosed with bipolar I disorder experience at least one manic episode (and typically, at least one major depressive episode as well). In this review, bipolar disorder refers to individuals with bipolar I disorder unless otherwise specified. Life events Dohrenwend and Dohrenwend (1981) suggested that stressful life events are those that are proximate to, rather than remote from, the onset of the disorder. Thus, the proximity? of a life event to the onset of a disorder is vital in order to assume its association with the onset, and particularly, as the trigger of a mood episode. In support of such a contextual model, recent research has suggested that social support, personality, and other psychosocial variables may act as third variables in the relationship of life stress and affective disorders (Leskela et al. Ezquiaga, Gutierrez, and Lopez (1987) define life events as circumstances punctually situated in time that induce stress and require the individual to use adaptation mechanisms? and chronic stress as adverse circumstances that act uninterruptedly over a prolonged time (p. For this reason, many of the research designs in this review only examined events that had a moderate or severe impact on the participant. One such improvement is a change from the use of self-report forms, or checklists of life events, to life event interviews conducted by highly trained interviewers based on the contextual model established by Brown and Harris (1978). These interview-based assessments are similar in that they utilize the contextual threat methods of Brown and Harris and, thus, elicit objective impact ratings for each event (Brown & Harris, 1978). Further, these life event interviews utilize similar procedures of assessment and possess good psychometric properties (Alloy & Abramson, 1999; Daley et al. Social zeitgebers and social rhythms the term zeitgeber,? German for time-giver,? is used to describe environmental, or external, time cues that entrain human circadian rhythms. For example, research has found that in free running environments, circadian rhythms, such as the sleep?wake cycle, have a period of approximately 25 h (Refinetti and Menaker, 1992; Wehr et al. Thus, circadian rhythms are likely entrained by zeitgebers in our environment in order to yield a period of almost exactly 24 h, even though the inherent, free running cycle is 25 h (Moore-Ede, Czeisler, & Richardson, 1983; Panda, Hogenesch, & Kay, 2002; Wever, 1979). These data are consistent with the social zeitgeber theory; however, they do not rule out the possibility of an internal trigger as well. Moreover, do changes in zeitgebers cause severe enough disruptions to trigger affective episodes? Social zeitgebers are usually derived from social contact with other individuals, but solitary activities can also be social zeitgebers for the circadian clock. For example, many activities may occur alone or with others, such as, commuting to work, having meals, bedtimes, and watching television (Monk, Kupfer, Frank, & Ritenour, 1991). In Ehlers, Kupfer, Frank and Monk (1993) the social zeitgeber theory was amended to include physical zeitgebers in addition to social zeitgebers. For example, light is a physical zeitgeber (or zeitstorer?) that can entrain and regulate the circadian rhythms of hormonal, metabolic, and physical activity, which has also been shown to have clinical implications for mood disorders (Panda et al. The measure is completed in the evening before going to bed and tracks the timing of 15 specific and 2 write-in, or individualized, activities. If the time an activity occurs on a given day is within 45 min of the average time, it is considered a hit. Average frequency of activities also often is calculated by averaging the frequencies of all items that had been endorsed as regular (possible range=3?7 times) (Monk et al. One study conducted two reliability assessments of this rating system for social rhythm disruption events and found high inter-rater agreement (kappa=0. Biological rhythms A biological process of the human body that repeats itself approximately every 24 h is considered to have a daily rhythm. Such rhythms are defined as circadian? if they persist with the same period in the absence of external time cues, or are endogenously driven (Refinetti & Menaker, 1992). These studies are interested in observing as many oscillations, or consecutive cycles, of the circadian rhythms as possible to understand the quantitative aspects of the rhythms. Participants in these studies are isolated from their normal environments for usually 10 to 30 d, although some studies may only isolate participants for a few days, particularly if a sleep manipulation is imposed (Minors & Waterhouse, 1985).

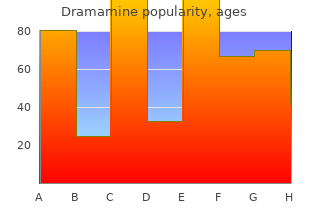

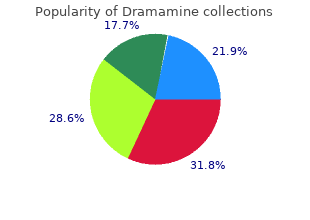

The approach used to discount dramamine 50 mg on-line symptoms 20 weeks pregnant estimate method-specific prevalence in 1994 and 2015 is described in annex I dramamine 50mg sale medications you can take when pregnant. In 2015 cheap 50mg dramamine medicine pill identification, 64 per cent of married or in-union women of reproductive age worldwide were using some form of contraception (figure 3 buy dramamine 50mg overnight delivery medicine quotes doctor, dark bars). However, contraceptive use was much lower in the least 1 developed countries (40 per cent) and was particularly low in Africa (33 per cent). Among the other major geographic areas, contraceptive use was much higher in 2015, ranging from 59 per cent in Oceania to 75 per cent in Northern America. Prevalence in 2015 was several times as high in Northern Africa and Southern Africa (53 per cent and 64 per cent, respectively) as in Middle Africa (23 per cent) and Western Africa (17 per cent). Contraceptive use has been increasing recently in Eastern Africa and now stands at 40 per cent. At the other extreme, Eastern Asia had the highest prevalence (82 per cent) of all the world regions in 2015, due to the very high level of contraceptive use in China (84 per cent). In the other regions of Asia, the average prevalence was in a range between 57 per cent and 64 per cent. Regional contrasts are smaller in Latin America and the Caribbean, although the level of contraceptive use was lower in the Caribbean (62 per cent) than it was in Central America (71 per cent) and South America (75 per cent). Within Europe, prevalence in 2015 was lowest in Southern Europe (65 per cent) and highest in Northern Europe (77 per cent). In Oceania, the level of contraceptive use in Australia and New Zealand was typical of levels in regions of Europe, whereas the level was much lower, 39 per cent, in Melanesia, Micronesia and Polynesia. At least one in ten married or in-union women in most regions of the world has an unmet need for family planning. Worldwide in 2015, 12 per cent of married or in-union women are estimated to have had an unmet need for family planning; that is, they wanted to stop or delay childbearing but were not using any method of contraception (figure 3, light bars). Many of the latter countries are in sub-Saharan Africa, which is also the region where unmet need was highest (24 per cent), double the world average in 2015. Unmet need in 2015 was highest (above 20 per cent) in the regions of Eastern Africa, Middle Africa, Western Africa, and Melanesia, Micronesia and Polynesia. Unmet need was lowest (below 10 per cent) in Eastern Asia, Northern Europe, Western Europe and Northern America. Given that survey data on unmet need for family planning are limited, especially for countries in Europe and Eastern Asia, the median estimates presented for 2015 have relatively wide 80 per cent uncertainty intervals (annex table I). Contraceptive use and unmet need for family planning levels vary widely across countries. Within Africa, countries or areas with contraceptive prevalence of 50 per cent or more are mainly islands (Cabo Verde, Mauritius and Reunion), or located in the north of the continent along the Mediterranean coast (Algeria, Egypt, Morocco and Tunisia) and in Southern Africa (Botswana, Lesotho, Namibia, South Africa and Swaziland) (figure 4). Five countries in Eastern Africa (Kenya, Malawi, Rwanda, Zambia and Zimbabwe) also had contraceptive prevalence levels of 50 per cent or more in 2015. In contrast, 17 countries of Africa had contraceptive prevalence levels below 20 per cent. This group includes the populous country of Nigeria, where contraceptive use was at less than half the level in Ethiopia (16 per cent and 36 per cent, respectively). Less than 10 per cent of married or in-union women of reproductive age were using contraception in Chad, Guinea and South Sudan in 2015. Contraceptive prevalence and unmet need for family planning among married or in-union women aged 15 to 49 years, 2015 Source: United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2015a). In 10 countries, contraceptive prevalence in 2015 was 70 per cent or more, with an estimated high of 83 per cent in China. In all, 37 of the 48 countries or areas in Asia with sufficient data to enable estimates had contraceptive prevalence levels of 50 per cent or more in 2015. The lowest level of contraceptive prevalence in Asia was in Afghanistan and Timor-Leste at 29 per cent. Contraceptive prevalence in 2015 was above 70 per cent in 13 countries of Europe as well as in Canada and the United States of America. However, three countries in Europe still have prevalence levels below 50 per cent (Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro and the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia). Similarly, most countries in Latin America and the Caribbean have at least a moderate level of contraceptive use. Of the 39 countries or areas with available estimates in Latin America and the Caribbean, only Guyana and Haiti had prevalence levels below 50 per cent in 2015, and 16 countries had prevalence levels of 70 per cent or more (Nicaragua had the highest level at 80 per cent). The most populous countries in the region?Brazil, Colombia, Mexico and Peru?all had contraceptive prevalence levels of 70 per cent or more. Among 16 countries or areas in Oceania, Australia and New Zealand were on one end with contraceptive prevalence levels of 68 per cent and 71 per cent, respectively, and 11 countries were on the other end with prevalence levels of less than 50 per cent in 2015. The percentage of married or in-union women estimated to have had an unmet need for family planning in 2015 ranges from less than 10 per cent in 36 countries across all major areas to 30 per cent or more in 15 countries concentrated in Africa (also including Haiti and Samoa) (figure 5). In 59 countries, at least one in five women on average had an unmet need for family planning in 2015, and 34 of these 59 countries are in Eastern Africa, Middle Africa or Western Africa. Worldwide in 2015, 57 per cent of married or in-union women of reproductive age used a modern method of family planning (see annex table I), constituting 90 per cent of contraceptive users. Among the 195 countries or areas with sufficient data to enable estimates, modern method prevalence ranged from 5 per cent or less in Chad, Somalia and South Sudan to 80 per cent or more in China and the United Kingdom. Modern methods were used by at least three in four contraceptive users in 148 countries in 2015, representing all regions of the world. However, modern methods constituted less than half of all contraceptive use in 11 countries, mainly concentrated in Middle Africa and Southern Europe.

Mechanisms of action buy dramamine 50 mg free shipping symptoms weight loss, effectiveness rates buy cheap dramamine 50mg line medicine in the middle ages, and side effects of artificial contraceptive methods Understanding the mechanisms of action of artificial contraceptive methods is critical for informed choice order dramamine 50mg visa treatment 911. Women must be aware of how these methods work to order 50mg dramamine fast delivery treatment 4 stomach virus prevent pregnancy in order to make truly informed decisions. Although included as a form of contraception, natural family planning? is more accurately a form of family planning, as it can be used to achieve or avoid pregnancy as well as to maintain health. Because these options vary widely, such as the many manifestations of the hormonal pill, a comprehensive analysis of their effectiveness is impossible here. The following is a general overview of these methods, their effectiveness, and their potential side effects. Short-term hormonal methods Short-term or temporary hormonal contraceptives, including the pill, the patch, and the ring, are commonly used methods due to their easy access and use. Failure to meet these conditions risks 215 pregnancy, and is also the reason for lower effectiveness. Combined estrogen-progestin contraceptives work by releasing hormones to inhibit ovulation 217 and can increase cervical mucus viscosity. Progestin-only contraceptives that release 218 levonorgestrel thicken the cervical mucus and do not always prevent ovulation. Desogestrel pills, Depo-Provera, and etonogestrel-releasing implants, types of progestin-only 219 contraceptives, also work by inhibiting ovulation. Combined contraceptives include the 220 combined oral contraceptive (often referred to as the pill?), monthly injectables, 221 transdermal patches, and vaginal rings. The first-year typical-use and perfect-use failure rates for combined pill and progestin-only pill, the Evra patch, and the NuvaRing (vaginal ring) are each 9 percent and 0. These short-term hormonal methods can result in a wide range of side effects and disruptions to the natural hormonal process that can mask underlying health problems and risk health problems, including infertility. The vaginal ring, for example, inhibits ovulation, an effect that 225 remains for weeks thereafter. Additional side effects among ring users include headaches, 226 vaginitis, and nausea. The synthetic progestins and estrogens used in hormonal contraception can cause side effects because they are not identical to natural progesterone and 229 estrogen. The hormones can have negative effects on carbohydrate metabolism and lipid and 230 lipoprotein metabolism and cause hypertension and deep vein thrombosis. Also, the estrogenic component of contraceptives can increase viral replication by acting at a 234 genomic level. The first-year typical-use and 251 perfect-use failure rates for Depo-Provera are 6 percent and 0. Another possible side effect of the Implanon is unscheduled bleeding patterns, which range 261 from amenorrhea and infrequent bleeding to irregular, frequent, and prolonged bleeding. Further, almost all women experience painful insertions 263 and insertion difficulty is common. A possible complication is uterine perforation, which, if it occurs, generally 265 occurs at the time of insertion. Barrier methods 267 Barrier methods include the male and female condom, the diaphragm, and the cervical cap. Perfect-use 270 failure rates are 2 percent for the male condom and 5 percent for the female condom. Sterilization Female sterilization is done by blocking the fallopian tubes in one of several ways: surgically 272 cutting, removing part of the tube, blocking with clips or rings, or electrically coagulating. Male sterilization is done through vasectomy, which blocks each vas deferens, preventing the flow of 274 sperm into semen. First-year typical use and perfect-use failure rates for female sterilization are 0. Failure rate post-sterilization 276 increases with time, since pregnancies can occur several years following the procedure. In one study, women less than 30 years old were four to six times more likely to experience regret than women aged over 30 years; a 5-year follow-up found that 4. It can take more than three months, or 12 to 20 282 ejaculations, for the ejaculate to be sperm-free. Furthermore, men experience an array of 283 side effects, among them sperm granuloma (lumps of sperm). Another side effect is orchalgia (chronic testicular 285 pain), the incidence of which is 12 to 52 percent. Emergency contraception Emergency contraception is designed for use after unprotected intercourse or intercourse with 286 failed contraception. Sexually transmitted infections No form of contraception, including barrier methods, can fully protect a woman from contracting or spreading a sexually No form of contraception, including barrier transmitted infection. Data from the Demographic and Health Surveys in developing countries show a mean coital frequency of 5. Coital frequency is affected by several factors, including age of each partner, marital duration, 303 marital quality, number of children, and socioeconomic status. A study of users of either of two fertility awareness methods found that the mean coital frequency was similar to that of users of other methods, with intercourse timed to coincide 304 with non-fertile days. The methods coital frequency was similar to that of users helped couples identify their fertile of other methods, with intercourse timed to periods, and researchers requested coincide with non-fertile days. Sexual desire and satisfaction Reviews of studies on the impact of hormonal contraceptives on sexual desire show varied 308 results, indicating it is difficult to predict how each woman will react.

We consider a period of less than 1 month of apparent well-being as a transition from one phase to cheap dramamine 50 mg with amex medications not to take during pregnancy its opposite dramamine 50mg with mastercard medications ranitidine, and not as a free interval cheap dramamine 50mg without a prescription 4 medications at walmart. We distinguish the cases with continuous circular course into those with long cycles (less than two per year) and those with short cycles (two or more per year order dramamine 50 mg with visa medications zopiclone, or four or more episodes per year). Continuous circular course with long cycles Eighty-three patients (19% of all bipolars) had this type of course, divided about equally between men and women. The majority of the group (47 patients: 26 men and 21 women) had hypomanic episodes between depres sions. The most typical patients of the group had an annual cycle, with depression in autumn and winter and mania (more often hypomania) in spring and summer. However, all combinations of lengths of the two phases Cyclicity and manic-depressive illness 327 were seen. Both depression and mania could be as long as 2 years, but the depression was generally much longer than the mania. Continuous circular course with rapid cycles Eighty-seven patients (20% of all bipolar patients) had a continuous circular course with rapid cycles (two or more per year). In this group the number of women was more than twice that of men (61 women and 26 men). Only 16 patients had one or more severe manias, while 71 had only hypomanic episodes. The depression was moderate and of the inhibitory type in only 11 cases, all of which had severe manias. The duration of the episodes was usually of 1?3 months, and depressions were slightly longer than hypoma nias. The transition from depression to mania was often very rapid, like a switch, while the transition from mania or hypomania to depression was often very gradual. In 20 patients (10 men and 10 women) the disease took the rapid circular course from the very beginning. In the other 67 cases the disease started with a different course, which lasted from 1 to 40 years before the establishment of the rapid circular course. As we shall discuss later, this change of course was in most cases associated with the use of antidepressants. In general it could be stated that treatment with an antidepressant action shortens the duration of the depressive phase but may trigger or accentuate a hypomanic or manic phase and shorten the following interval (Altshuler et al. Patients with this type of cycle rarely become rapid cyclers but if continuous antidepressant treatments are administered they may cause an anticipated provocation of a mania and eventually rapid cyclicity. Antimanic treatment suppresses the excited phase of the cycle but may aggravate the following depression. Neuroleptic treatment of mania is probably responsible for many of the post-manic depressions seen today, and it could explain the discrepancy in frequency of recurrent mania between studies carried out before the neuroleptic era and more recent ones. The underlying link between mania and the following depression was well understood by Aretaeus (1735), as seen in the quotation above, and by Pinel (1809) who writes: "The attacks [of mania], after lasting through the hot season and ending towards the end of autumn, cannot fail to bring on a sort of exhaustion marked by a general feeling of lassitude, prostration that sometimes goes as far as syncope, an extreme confusion of ideas and in some cases a state of stupor and insensibility, or rather a gloomy moroseness and the deepest melancholy. In these cases it is clear that lithium prevents depression by suppressing or preventing the onset of mania. This poor response should be attributed in large measure to the action of antidepressant drugs given during the depressive phase; this action often causes a rapid switch from depression to mania or hypomania, and a temporary refractoriness to lithium of the mania or hypomania. Patients with the continuous circular course are known to respond less well to treatment than patients with more or less long intervals. This could be attributed to the effects of the treatment of one episode upon the subse quent one. Anti-manic treatment aggravates the following depression, and antidepressant treatment accentuates the following mania or hypomania. These two varieties of mania and melancholia which when they run isolated are usually more curable than the others, present the greatest severity when they run together to form the folie circulaire. These cases have become more frequent in recent years, in the years of antidepressant drug treatment, than before. In most cases (70%), rapid cyclicity is not spontaneous but develops later in the course of the illness, in associa tion with treatment by antidepressant drugs. Other patients start with recurrent depression and, in association with antidepressant treatment, become bipolar and eventually rapid cyclers. The common feature of the transformation of previous courses into rapid cyclic ones is the appearance for the first time in the course of the disease of a hypomanic episode after the depression, or the accentuation of a hypomania that had been of a milder intensity in previous recurrences. It is after one or more such depres sion?hypomania cycles (more rarely, depression?mania) that the following depression occurs without interval and that continuous circularity is established. Table 3 shows the outcome of 96 rapid cycling patients after more than 5 years of follow-up (range 5?32 years); 34% of them were still cycling rapidly while another 14% had became long cyclers but still very resistant to stabilizing treatments. By 1997 only 32% had reached full remission (Koukopoulos 1997) after many years of intensive mood-stabilizing treatments. Others will shout with joy or dissolve in tears at the slightest provocation, and others again are moved by a few things only, but these the more deeply and lastingly. All this indicates that there is something that decides the moods of the soul: this is the degree of vitality of the temperament. The four basic temperaments were the melancholic, the sanguine (hyper thymic), the choleric (irritable) and the phlegmatic. Through the contribu tions in modern times of Kraepelin (1913), Kretschmer (1929), Schneider (1962), and in recent years of Akiskal et al. Girardi are today considered the depressive or dysthymic, the hyperthymic, the irritable and the cyclothymic. The cyclothymic is certainly not the equivalent of the phlegmatic one; indeed, it is its opposite in every respect.

Dramamine 50 mg on-line. What are the symptoms of a retinal detachment?.