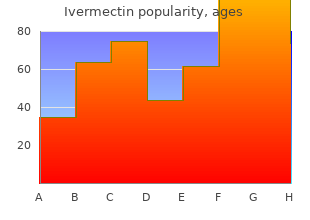

Ivermectin

"Buy ivermectin 3 mg low cost, antibiotics for acne worse before better."

By: Richa Agarwal, MD

- Instructor in the Department of Medicine

https://medicine.duke.edu/faculty/richa-agarwal-md

In fact cheap ivermectin 3mg with amex antibiotic ladder, medical practice has already radically changed to order ivermectin 3 mg without prescription antibiotic growth promoters recognize this awareness of the importance of early diagnosis cheap 3 mg ivermectin fast delivery bacteria 1 urine test. Soon after birth discount 3 mg ivermectin mastercard antimicrobial susceptibility, babies are given an acoustic test that indicates whether they have an auditory dysfunction. With an early diagnosis of possible deafness, parents can be attentive to those aspects and improve their children�s social development. Something similar happens with dyslexia: the cerebral response to phonemes�at one year old�is indicative of the difficulties babies might encounter almost four years later, when they begin learning to read. The subject is so sensitive and delicate that it is tempting simply to turn a blind eye to it. Decisions made by default�by not doing anything�might feel easier to make but do not side-step the need to take responsibility. One thing is for sure, a near future in which we will be able to estimate the likelihood that a child will develop dyslexia is imminent. What we must decide�at all levels of society, from parents, to teachers and head teachers, to policy makers�is how to act on this information. My opinion is that information about the likelihood of dyslexia can be used carefully and respectfully, without stigmatizing children. It is good for parents and educators to know if a child has a significant probability of having difficulties in reading. This will allow them to give the child the opportunity to do some phonological exercises (which are completely innocuous and even entertaining) that might help in overcoming that initial disadvantage, in order to learn how to read, so that they have better prospects when starting the first year of school, with the same possibilities as the rest of their classmates. To sum up: (1) Phonological awareness, which has to do with sound and not sight, is a fundamental building block of reading. Children who have low resolution in their phonological systems show a predisposition for dyslexia. The study of reading development is one of the most prominent cases of the way in which investigation of the human brain can be useful to educational practice. It is at the core of this book�s intention to explore how this reflective exercise on the part of science can help us to understand ourselves and communicate better. What we have to unlearn Socrates questioned what common sense suggests, that learning consists of acquiring new knowledge. Instead, he proposed that it involved reorganizing and recalling knowledge we already have. I now put forth an even more radical hypothesis of learning understood as a process of editing, as opposed to writing. Erasing things that take up space uselessly and others that, even worse, are a hindrance to effective thought. Compared to other �mistakes� that children make when learning, this one is often overlooked, like some sort of endearing temporary clumsiness. In fact, just try to write an entire sentence backwards, the way kids do naturally. But since objects turn and rotate, the visual system is not very interested in their particular orientation. Alphabets inherit the same fragments and segments of the visual world, but their symmetry is an exception. For example, almost everyone remembers that the Statue of Liberty is in New York, that it is somewhat greenish, that it has a crown and one hand raised with a torch. Most people can�t remember which it is, and those who think they do are often wrong. It makes sense that we forget those particular details, since our visual system has to actively ignore these differences in order to identify that all the * rotations, reflections and shifts of an object are still the same object. The human visual system developed a function that distinguishes us from Funes the Memorious and makes us understand that a dog seen in profile and a dog seen head on are the same dog. It was later in the history of humanity that alphabets appeared, imposing a cultural convention that goes against the grain of our visual system�s natural functioning. Those who are learning to read still function with a default setting in their visual systems, in which the �p� is equal to the �q�. And part of the process of learning implies uprooting a predisposition, eradicating a vice. We have already seen that the brain is not a tabula rasa where new knowledge is written. And as we just saw in the case of reading, some spontaneous forms of functioning can result in idiosyncratic difficulties in learning. The framework of thought From the day we are born the brain already forms sophisticated conceptual constructions, like the notion of numerosity, and even morality. When we listen to a story, we don�t record it word by word but rather we reconstruct it in the language of our own thoughts. The same thing that happens with a film occurs with a class; each student reconstructs it in their own language. Our learning process is a sort of convergence point between what is presented to us and our predisposition for assimilating it. The brain is not a blank page on which things are written, but rather a rough surface on which some shapes fit well and others don�t. The Greek cognitive psychologist Stella Vosniadou studied thousands and thousands of drawings in detail to reveal how children�s representations of the world change. At some point in their educational history, children are presented with an absurd idea: the world is round. The idea is ridiculous, of course, because all factual evidence accumulated over the course of their lives * points to the opposite. In order to understand that the world is round one must unlearn something very natural based on sensory experience: the world is clearly flat. But this in turn brings new problems; why doesn�t the world fall if it is just floating in space

Because primatologists are able to buy discount ivermectin 3mg bacteria klebsiella infections identify individuals on hearing their pant-hoots cheap ivermectin 3mg on-line antibiotic during pregnancy, it is presumed that chimpanzees can too buy cheap ivermectin 3mg on line antibiotics dizziness. In addition to 3 mg ivermectin free shipping antimicrobial benzalkonium chloride revealing locations of individual animals, long-distance pant-hoots announce food sources or threaten individuals in other communities. Goodall (1986:134) noted that pant-hoot choruses may break out during the night, passing back and forth between parties that are sleeping within earshot. Besides such �singing,� chimpanzees sometimes engage in drum ming displays by pounding hands and feet on large trees. Drumming is, again, done primarily by males and is typically accompanied by pant hoots (Goodall 1986:133). Although chimpanzees are naturally chatty, they actively suppress their vocalizations under some circumstances, such as when males go on patrols of territorial boundaries. Their calls, however, are not strictly referential, unlike vervet alarm calls, and this fact more than any other reveals the limits of vocal communication in our nearest nonhuman primate cousin (Mitani 1996). These comparative observations, together with evidence pertaining to the anatomy of the vocal tract (Frayer and Nicolay, this volume) and cerebral cortex (Falk 1992a, b) of fossil hominids, allow one to form reasonable speculations about auditory communication in our earliest 211 Hominid Brain Evolution and the Origins of Music hominid ancestors, the australopithecines. Minimally, they should have possessed a rich repertoire of calls employed in social contexts and used especially to express emotions. That is, rather than being referential as words are, their calls (entailing pitch changes) would have been gener ally emotive and affective. In addition, australopithecines probably did a certain amount of chorusing and drumming, similar to African great apes. It is possible that early hominids were also characterized by gender differences in their auditory communications, although no evidence pertaining to this is found in the fossil record to date. In short, modern linguistic and musical abilities probably evolved from beginnings such as these. A hint at how humanlike auditory communication evolved may be glimpsed by examining neurological substrates for auditory-vocal com munication in people and other animals. As documented, humans are, above all else, highly lateralized for processing language and music, respectively, to left and right hemispheres. Unlike any other animal, including nonhuman primates (McGrew and Marchant 1997), Homo sapiens is also highly lateralized for right-handedness, the neurological substrate of which is adjacent to Broca�s speech area in the left hemi sphere. Con trary to previously held beliefs, other species are also neurologically lateralized for a variety of functions, including circling behaviors in rodents, production of songs in birds (left hemisphere dominant), and processing of socially meaningful vocalizations (left hemisphere domi nant) as well as certain visual stimuli (dominance varies with task) in some monkeys (Glick 1985; Falk 1992a, b). Furthermore, it is the rule rather than the exception for these asymmetries to be sexually dimor phic with respect to side of dominance and/or frequency of occurrence (Glick 1985). From these data, we may surmise that complex human auditory communications evolved as hominid brains enlarged beyond the ape-size volumes characteristic of australopithecines (Falk 1992a, b), in conjunction with elaboration of basic cortical lateralization that was inherited from very early mammalian ancestors. If one can discern a basic function for brain lateralization in animals, one might have a glimmer about why language and music eventually evolved in humans. In this context, it becomes important to explore Darwinian natural selection by assessing reproductive advantages that are gained by individuals or species as a result of lateralization. Within this framework, the gender differences in brain lateralization that char acterize many species (Glick 1985) are tantalizing. For example, a study in the house mouse (Ehret 1987) offers an important clue about the pos sible evolutionary history of the neurological substrates that facilitate enhanced language skills in women relative to men (Falk 1997). Clearly, there should be a strong selective advantage for these mothers, that is, more of their offspring will survive. In a polygynous species of another small rodent, the meadow vole, males have enhanced visuospatial skills that apparently bene t them during mating season when they travel in search of mates (Gaulin and FitzGerald 1989). Similarly, male songbirds use lateralized singing to attract mates (Slater, this volume), thus increasing their reproductive tness. These ndings are suggestive in light of men�s relatively greater lateralization for both singing and visuospatial skills, and women�s rela tively enhanced language and social skills. Limited as they are, these and other data (Falk 1997) suggest that mammalian brain lateralization may be rooted in different reproductive strategies for males (put energy toward nding mates) and females (devote efforts to raising offspring). It is not surprising, then, that aspects of language, music, singing, and visu ospatial skills that evolved from a basic mammalian brain plan are lat eralized differently in brains of men and women. It is even possible that neurological substrates for these activities are wired differently because the two sexes continued to depend on different reproductive strategies during the past ve million years (Falk 1997) or even more recently (Miller, this volume). Returning to the African apes, one could almost argue that a chorus of rising and falling pant-hoots, or pant-hooting accompanied by drum ming on trees, is tantamount to a kind of protosinging or protomusic. It is more dif cult to view ape vocalizations as representative of protolan guage, however, because of the lack of referential calls (Mitani 1996). Clearly, apes are not capable of projecting chopped up bits of air from their mouths (phonemes) that can be recombined in an in nite number of meaningful utterances; their vocalizations manifest neither the seman ticity nor the productivity of human language. If one asks when humanlike as opposed to apelike music rst appeared, the discussion regarding the neurological bases of music and language outlined above, as well as paleoneurological evidence from the hominid fossil record dis cussed below, have important implications for the answer. Results from brain imaging studies may be interpreted as implying that music and language are part of one large, vastly complicated, dis tributed neurological system for processing sound in the largest-brained primate. Both systems use intonation and rhythm to convey emotions, that is, affective semantics (Molino, this volume). Both rely on partly 213 Hominid Brain Evolution and the Origins of Music overlapping auditory and parietal association cortices for reception and interpretation, and partly overlapping motor and premotor cortices for production. Music and language can both be produced by mouths or by tools, and each is processed somewhat differently by men and women.

I could dampen the fallout from the circumstances outside my control by being nice and funny order ivermectin 3 mg on-line virus ebola, or striking up a conversation when I felt it was appropriate cheap ivermectin 3mg online antibiotic question bank, but the customers still blamed me when something went wrong order ivermectin 3mg on-line bacteria reproduce asexually. When you are at a restaurant buy 3mg ivermectin otc virus yahoo, you have a hard time seeing through to the personality of the server. Sometimes you are right, but often you are committing the fundamental attribution error. Have you ever watched a quiz show like the Weakest Link or Jeopardy and thought, however briefly, that the host was super-smart Perhaps there are a handful of musicians, or authors, or professors in your life you�ve placed on a pedestal. You imagine how difficult it would be to hold your own in conversation with these people, as you imagine their towering intellect would crush you as you resorted to prattling on about pasta recipes and your collection of ornate spoons. When you don�t know much about a person, when you haven�t had a chance to get to know him or her, you have a tendency to turn the person into a character. You are a different person with your friends than you are with your family or your boss. You perpetrate the fundamental attribution error just about every time you read a news story. For instance, every once in a while, someone snaps and goes on a killing spree at the post office. Sometimes they still work for the United States Postal Service, sometimes they are recently fired. Movies, books, television shows, and even pop music continue to refer to postal workers going on rampages, as recently as 2010. Many explanations have been offered for the phenomenon, ranging from stress at the workplace to a frustrating bureaucratic grievance process and the copycat effect. The truth, however, is people are always snapping and going on shooting sprees in the modern United States. There are lists available online of three hundred or more incidents, and you can Google the term �shooting rampage� any time of the year and be guaranteed a mass murder will appear from within the last few weeks. Oddly enough, the homicide rate at post offices is actually lower than in retail, but that�s probably because people in retail are more likely to be killed in a robbery. At any rate, the reason you are familiar with the idea of a lone postal worker killing all his coworkers is that the national media tends to cover these incidents no matter where they occur. When you hear about a shooting like those at the post office or in a school or at an airport, what is the first thing you assume about the killer You don�t want to think potential killers are all around you, or you yourself could lose it in such a grand and total way. Yet, most of the time, the people who snap don�t wake up one day with murder on the brain. They build an identity around their jobs and think they�ve lost everything when they get fired. They often suffer from a sense of anomie and isolation and believe they can go out in a blaze of glory. Many feel as if they�ve been tormented and shamed for too long and want to settle a score. For you, on the outside, it is easier to blame the personality of the murderer as if that person was bound to kill one day no matter what. As distressing as it may be, it is another way the fundamental attribution error drives you to jump to conclusions. You see the person, and ignore his or her surroundings, and then cast blame on only the individual. It�s an unpleasant thought to imagine evil could be more the result of a series of terrible events and social pressures than the working of a deviant mind. Knowing this is so does in no way excuse those who harm others, but nevertheless it seems to be true. There was a class clown and a slacker, a misanthropic poet and an energetic politician striving for grades. Movies and books with a cast of characters make sense to you because in life you tend to turn everyone into a character whose behavior is predictable. You are always aware of the minds of others and are always searching for an explanation as to why people are behaving the way they do. Psychologists know most behavior is the result of a tug-of-war between external and internal forces. You seem like a different person at work than at home, a different character at a party than you are when you�re with your family. On paper, this seems like common sense, but you easily forget about the power of the setting when judging others. Instead of saying, �Jack is uncomfortable around people he doesn�t know, thus when I see him in public places he tends to avoid crowds,� you say, �Jack is shy. Seeing people through the lens of their situation is one of the foundations of social psychology, where it is referred to as attribution theory. If someone walks up to you in a bar and offers to buy you a drink, the first thoughts in your mind won�t be an analysis of the person�s face or the temperature in the room. You can�t be sure of the answer, so it shifts and bounces from one possibility to the next. When you see a behavior, like a child screaming in a supermarket while the seemingly oblivious parents continue to shop, you take a mental shortcut and conclude something about the story of their lives.

Ivermectin 3mg otc. CBD Kills Antibiotic Resistant Bacteria.